©Andy: A Tridacna crocea partially exposed by a Maori Wrasse, showing the depth of penetration into the coral by the clam

Colours

Distinguishing features

The smallest and most abundant of the Giant Clam. The shell is white in colour on the GBR, though in part of Asia it may be pinkish-orange to yellow on both the inside and outside of the shell. This species has a very distinct triangular ovate shell (from a side view) with closely spaced scales near the shell edge, and a very wide byssal orifice. The byssal attachment is strong and the clam burrows into the coral substrate, with only the mantle and the top edge of the shell protruding. Mantle colour is variable, but most commonly a dark blue-brown. Distinguish from other species of Tridacna by the small size and deeply embedded habit.

Size

- Up to 15 cm (Length of specimen)

Synonyms

Comments

Guardians: Sarah Davies and Sheridan Pym

by David Witherall

Interesting facts

- The Burrowing Clam starts its life as a planktonic larvae that looks like a tiny clam with big swimming ears (velum). When ready, it smells out a suitable place to land (prefers one with other clams already on it) and then lets out acid to melt itself into the rock.

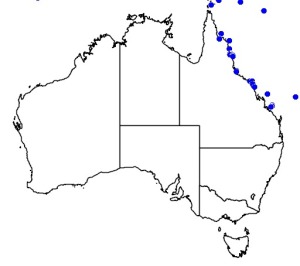

Distribution

Distribution and habitat preferences

Protected shallow back reef, lagoonal, and reef flat habitats. Not generally seen below about 5-6m.

Abundant in shallow habitats around Lizard Island.

Behaviour

Like other Tridacnid clams, this species is a hermaphrodite, with the male testes forming first at about 2 years of age, followed by the female ovaries a year or so later. Tridacnid clams spawn in the warm summer months between October and February, usually during neap tides when water movement is minimal. This allows enough time for adequate mixing of the gametes. Spermatozoa are usually released first, with eggs only released if the animal detects the presence of sperm from a conspecific clam in the water column. Hence, reproduction is most successful when the animals are located in natural clusters. Eggs are only 100µm (1/10th of a mm) in diameter, and several million are released by each clam during a spawning event. Fertilisation is external, and a trochophore larvae hatches after about 12 hours. A bivalved veliger larvae develops after 48 hours, with a shell length of 160µm. This stage feeds on plankton and continues to swim in the water column, although it periodically ventures down to assess the conditions on the benthos. The veliger larvae settle permanently to the substratum at about 9 days of age and about 200µm, and the juvenile clams may reach 20-40mm shell length after their first year. Growth accelerates after this point, however mortality in the first few years is very high, with predation by fishes being a major factor.

Tridacnid clams obtain over 95% of their food requirements from the sugars produced by the symbiotic dinoflagellate algae (zooxanthellae) that inhabit the outer mantle tissue. Juvenile clams acquire the zooxanthellae directly from the water column at the time of settlement, and the algae live in tubules that are tertiary extensions of the gut and extend throughout the mantle tissue. Like hard corals, Tridacnid clams may bleach and lose most of their zooxanthellae after high temperature stress.

Web resources

References

- Griffiths, D.J., H. Windsor and T. Luong-Van (1992). Iridophores in the mantle of Giant Clams, Australian Journal of Zoology, 40: 319.

- Hirose, E., K. Iwai and T. Maruyama (2006). Establishment of the photosymbiosis in the early ontogeny of three giant clams, Marine Biology, 148: 551-558.

- Norton, J.H., M.A. Shepherd, H.M. Long and W.K. Fitt (1992). The zooxanthellal tubular system in the Giant Clam, Biological Bulletin, 183: 503-506.

- View all references